During a casual bout of toilet scrolling, I stumbled across a reel about Brazillian football superstar Neymar. In a monotonous drone, the voiceover spoke about Neymar’s immense talent and dramatic fall from grace, ending with the solemn conclusion that his story is a tragedy of unrealised potential. For a video about someone kicking a ball around, it all felt strangely bleak.

I chuckled. Anyone famous enough to fetch multimillion-dollar salaries and have entire videos made about them should be doing quite alright. And if what the reel said about his accomplishments were even half true, shouldn’t he be considered among the top 0.0001% of the sport?

I scrolled on. The football star popped up again. This time, he was being compared to Pelé—the Brazilian icon from the 60s whose explosive play cemented his place as one of the greatest footballers in history.

I knew about Pelé’s glory days, but the comparison still felt absurd. Can’t they both just be great in their own way? And why are we so weirdly upset that Neymar “fell short” of what he could achieve?

I was sure other people found the comparison just as brainless and rage-baity. I pull up the comments.

Comparing this clown to Pelé is an insult to the greatest. Brazillian football died with Pelé.

Neymar fell off. He doesn’t even want to play anymore.

I used to be such a big fan. Neymar really let the world down.

Huh. Okay.

I scrolled to the next reel—it’s Neymar again, accompanied by the same mournful voiceover, same tale of wasted potential. Next. Oh no, I think the algorithm’s caught on.

I exited the app.

Crimes against humanity

One-hit wonder. Washed-up. Has-been.

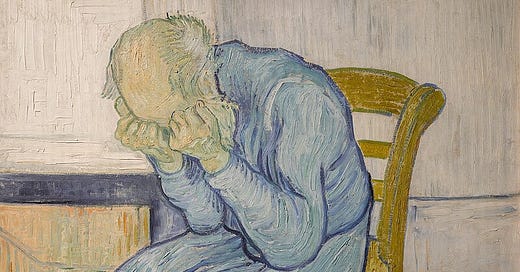

From sports to music to art, the world is littered with people branded by these dismissive labels. These were the ones whose early sparks of brilliance once drew attention, but were ultimately shelved as anomalies or written off as flukes. Many faded into obscurity, reduced to cultural footnotes and occasionally name-dropped at awkward dinner conversations (if they were even famous enough). They were the extraordinary ones, until the world collectively decided they weren’t anymore.

What’s funny—if not slightly disturbing—is how quickly society turns on these people. Despite doing nothing to deserve such scorn, they become targets of mockery and cautionary tales for our children. We look at them the way disapproving parents might glare at a lazy child, as if failing to "live up to potential" were some crime against humanity. And before long, we take it upon ourselves to write their eulogy of wasted potential: Utter disappointment. Try harder next life.

Okay, maybe not that dramatic—but you get the point.

Still, there’s a subtle but important difference between feeling let down when your favourite artist releases a dud and treating their “failures” like a personal affront. What happened to valuing effort, growth, or creativity for their own sake? Why are we so quick to write people off the moment they stop meeting our idea of greatness?

To understand this strange phenomenon, we might need to look inward.

Trade me your love

While brainstorming for this new issue, one thought wouldn’t leave me alone: I need to write something better than the last.

In the weeks that followed, every time I sat down to write, that thought paralysed me. Each new idea was constantly held up against what had come before. Is it more interesting? More meaningful? Will it get more reads?

Then I came across those reels criticising Neymar, and reading the comments felt eerily familiar—just like listening to the chorus of voices in my own head. In hindsight, it was painfully obvious: I had been judging myself with the same unforgiving lens, holding myself to impossible standards without ever stopping to question just how unfair that really was. For all the time I spent reflecting, it took watching someone else be torn apart for me to realise just how ruthless my own inner critic had become.

The irony? I was chasing perfection while believing that nothing I made would ever be good enough.

Perfectionism: n. the tendency to demand of others or of oneself an extremely high or even flawless level of performance, in excess of what is required by the situation.

— American Psychological Association

Our fixation on perfection might just be where all this fuss begins. It’s what makes us so quick to tear down those who keep showing up and trying and creating. Instead of acknowledging their effort, we impose our inflated expectations on them and criticise what was never broken in the first place. In the eyes of a perfectionist, even perfection may never be quite enough.

The causes of perfectionism are varied, but they often trace back to a common root: the belief that love is conditional—a reward to be earned through perfection. And when love is repeatedly experienced this way, we begin to internalise the idea that we must be exceptional to be worthy of affection or acceptance. It’s a deeply damaging belief, one that makes us hypercritical of both ourselves and others, even when we know that perfection is an impossible standard.

Self-oriented perfectionism is imposing an unrealistic desire to be perfect on oneself. Other-oriented perfectionism means imposing unrealistic standards of perfection on others. Socially-prescribed perfectionism involves perceiving unrealistic expectations of perfection from others.

— Psychology Today

I’ve long suspected that I carry a streak of perfectionism when it comes to writing—I procrastinate endlessly, constantly compare myself to others, and obsessively reread every sentence while overthinking each word and punctuation mark. At first, I thought I was simply taking things a little more seriously than most. After all, wanting to do well is human, right? But somewhere along the way, the impossibly high standards I held for myself had stopped pushing me forward and started holding me hostage.

Without realising it, I had become my own harshest critic.

Be human

For all its flaws, perfectionism isn’t inherently bad. At its best, it drives us to set ambitious goals and pushes us to pursue excellence with intention and care. The trouble only begins when those standards become rigid and unforgiving, and we start punishing ourselves for every minor misstep. The key here is to learn to let go of the impossible need to be flawless.

Before we can move forward though, it helps to look back and examine the early experiences that shaped our perfectionist tendencies. Was it a teacher* who only praised the top scorer? A parent whose love seemed to hinge on your achievements? Or a moment of exclusion that made you feel not quite enough? Ask yourself: What am I afraid will happen if I fail? Then challenge those assumptions. Are they rooted in truth, or are they simply beliefs you’ve mistaken for facts?

Perhaps the most powerful antidote of all is this: get comfortable with being average. Get comfortable with thinking, creating, and doing—not for recognition or validation, but because it matters to you. Learn to appreciate the quiet dignity of effort, even when the outcome is nothing like what you imagined. Things can be ordinary. People can be ordinary.

And that’s not a death sentence.

If a thing is worth doing, it is worth doing badly.

— G.K. Chesterton

*Fun story: My Primary 2 form teacher taught English—a language I was still learning as a second language. She never explicitly singled me out, but it was obvious she didn’t like me because I struggled with it. At the time, I didn’t understand why she treated me differently, so I poured my energy into improving my English, hoping to earn her love and approval. Looking back, I’m pretty sure this experience contributed to my self-oriented perfectionism, among other things. 🙃

P.S. It feels especially fitting to be writing about perfectionism in Issue 10—a number so often linked with the idea of perfection.

Cool stuff you should check out 🩸

The Root of All Cruelty? [essay]: A Psychology professor presents the uncomfortable idea that perhaps our worst acts of inhumanity stem from seeing others as human.

The AI Wedding No One’s Talking About [essay]: What happens when billionaire-manufactured realities start to shape what we believe?

On agency [essay]: A lot of life’s problems can be easily navigated if we weren’t so stuck on what the solution should be.

Saltburn [movie]: Oliver Quick is an outsider—but that doesn’t mean he won’t fit in. A beautifully wicked tale of privilege and desire.

The Lore of Elden Ring [videos]: Honestly super interesting even if you’ve never heard of the game or know anything about it.

SOMA [game]: An unsettling story about identity, consciousness, and what it means to be human.

Titan: The OceanGate Submersible Disaster [documentary]: A deep dive into the catastrophic decisions leading up to the fatal accident in 2023.