Issue 08: I finally watched Oldboy. Let's talk about it.

"Even though I'm no better than a beast, don't I have the right to live?"

This issue discusses the 2003 South Korean movie Oldboy. There are major spoilers ahead, so skip this if you’re planning to watch it!

Few films evoke such conflicted emotions in viewers as Park Chan-wook’s genre-defining Oldboy. Since its theatrical release more than two decades ago, the neo-noir flick has amassed millions of fans worldwide, with many hailing it as one of the greatest cinematic masterpieces of all time. Even award-winning filmmaker Quentin Tarantino named Oldboy his favourite film, going so far as to campaign for it to win the Palme d’Or at the 2004 Cannes Film Festival. Across generations and cultures, the film’s acclaim seems undeniable—Oldboy is good cinema.

But what exactly makes it so “good”? To find out, I had to see it for myself. So, on an otherwise uneventful Tuesday night, my boyfriend and I queued up the movie. Over its 120-minute runtime, we laughed, flinched, and occasionally gasped in horror. When the credits finally rolled, we sat back in stunned silence. Then I blurted out, “What the fuck did I just watch?”

My reaction was completely genuine, and I was in awe of the emotions this film managed to stir within me. In the moments that followed, I knew exactly what I had to do: write about it. So here I am—let’s dive in!

Here’s a quick synopsis of the story for anyone who needs a refresher: Businessman Oh Dae-su’s life takes a dark turn when, after being arrested for public drunkenness on the night of his daughter’s birthday, he is abducted and imprisoned in a grim hotel room. With only a television for company, he endures 15 years of isolation and failed suicide attempts, with no explanation for his captivity. Then, without warning, he is released. Determined to uncover the truth, Dae-su dives into a relentless search for his captor, only to discover that his imprisonment was just the first move in a sinister game.

For a full summary of the plot, you can refer to this Wikipedia article.

The following is an exploration of the themes I found most interesting during my viewing of Oldboy. Feel free to leave your thoughts in the comments.

Bad v. Evil

In mainstream cinema, we usually get a main character we can cheer for. But in Oldboy, that's not really the case.

The film opens with Oh Dae-su clutching a man’s necktie while he dangles dangerously from a building ledge. The music makes it feel like a big heroic moment, and for a second you might even think, “Okay, this guy’s pretty cool.” But then, as soon as he says his name, the scene cuts to a flashback in a police station, where we see him drunkenly stumbling and making a complete fool of himself. Amid the chaos, we quickly learn that it's his daughter’s birthday, which immediately paints him as an irresponsible father. In just the first five minutes, Director Park makes it clear: Oh Dae-su is a deeply flawed man.

As the film goes on, we’re reminded again and again of how flawed Dae-su really is. When confronted with a stranger on the verge of suicide, Oh Dae-su chooses to turn a blind eye rather than offer any compassion. At one point, while locked up, he has a moment of self-reflection and laments, "I thought I'd lived a simple life. But I've sinned too much." Later, when he receives a call from his kidnapper, he rattles off a list of names in a way that’s both kind of funny and revealing about his broken character.

These flaws also surface in the way he treats others. His despicable attempt to assault the woman who saved him, coupled with the cold, brutal way he seeks revenge, paints him as a selfish anti-hero. Hell, even his best friend Joo-hwan feels like a sleazy good-for-nothing. By this point, the audience is left questioning whether Oh Dae-su’s quest for vengeance is even justified. This sense of unease gradually builds throughout the film until we finally realise that the story being told is not one of good versus evil, but of bad versus evil.

The more I think about it, the more I question whether Oh Dae-su ever truly cared about his daughter. He missed her birthday for a night of drinking, and when he found out she’d been adopted overseas, he gave up looking for her without hesitation. Even when he discovered the horrifying truth, he chose to hide their incestuous relationship from her—a decision that seems to be driven less by paternal love and more by possessiveness. To me, Oh Dae-su doesn’t love his daughter, he just loves the idea of it.

The imaginary is very real

Seneca once wrote, “There are more things likely to frighten us than there are to crush us; we suffer more often in imagination than in reality.”

Worrying is a uniquely human trait, and Director Park cleverly weaves this idea into his exploration of human nature. In one pivotal moment of the film, Oh Dae-su is forced to face the consequences of his earlier violence. One of the thugs, revelling in his fear, delivers a sardonic piece of advice that highlights this theme saliently:

You see… they say that people shrivel up because of their imagination. So do not imagine anything. You'll become brave as hell.

Indeed, our imaginations have a way of making us cower in fear and spiral into anxious worry. When we expect the worst, we become slaves to our own illusions. More often than not, the scenarios we dread never actually become reality, yet we stupidly subject ourselves to unnecessary psychological torment.

To me, Lee Woo-jin and his sister are the most tragic victims of this human affliction. The thought of bearing a child from their incestuous relationship seemed to haunt them far more than the reality that she wasn’t actually pregnant. It’s almost heartbreaking how this imagined fear manipulated her body into showing signs of pregnancy, which only fuelled their anxiety further. That constant, overwhelming fear eventually drove them to make a devastating choice, leading to one of Lee Woo-jin’s most iconic lines: “Your tongue got my sister pregnant! It wasn't Lee Woo-jin's dick; it was Oh Dae-su's tongue!”

The power of our imagination is incredibly strong, and while it can often lead us down dark paths, I like to believe it can also be a force for good. Instead of imagining the worst, what if we used that energy to imagine all the incredible things we could achieve? I mean—look at what Oh Dae-su managed to do!

There are no winners

In traditional action epics like the James Bond movies, audiences revel in the satisfaction of seeing the villains get their just desserts. In Oldboy, Director Park Chan-wook takes a sharp turn away from this supposedly badass revenge odyssey and instead forces viewers to confront the absurdity of revenge itself.

Take the iconic one-take corridor scene: Oh Dae-su fights his way through a mob of thugs using only a hammer. At first, it feels heroic—almost exhilarating—but as the fight drags on, something shifts. You start noticing how clumsy he is, how awkwardly he swings his weapon. It stops feeling heroic and instead reminds you of the moment earlier in the film when he was drunkenly flailing about, throwing a tantrum in the police station. This parallel is intentional; Director Park strips away any sense of grandeur, reducing the fight to a messy, almost comical standoff. By the end, the thugs are lobbing their weapons at Oh Dae-su in sheer desperation as he awkwardly stumbles backward. The whole scene is less "action hero" and more dark comedy.

And it’s not just Oh Dae-su’s revenge journey that feels pointless. When we finally uncover the full scale of Lee Woo-jin’s so-called “master plan,” the absurdity reaches new heights. Surely, locking someone up for 15 years must stem from some unforgivable offence, right?

Spoiler: it’s not. And this is the genius of Oldboy—the revenge never should have happened at all. By every metric, Lee Woo-jin is a man who has everything—money, power, success. Yet he spends decades consumed by hatred for a man who doesn’t even remember him. In the end, when all was said and done, he finally asks the question we’ve all been expecting: “Now, what will I live for?”

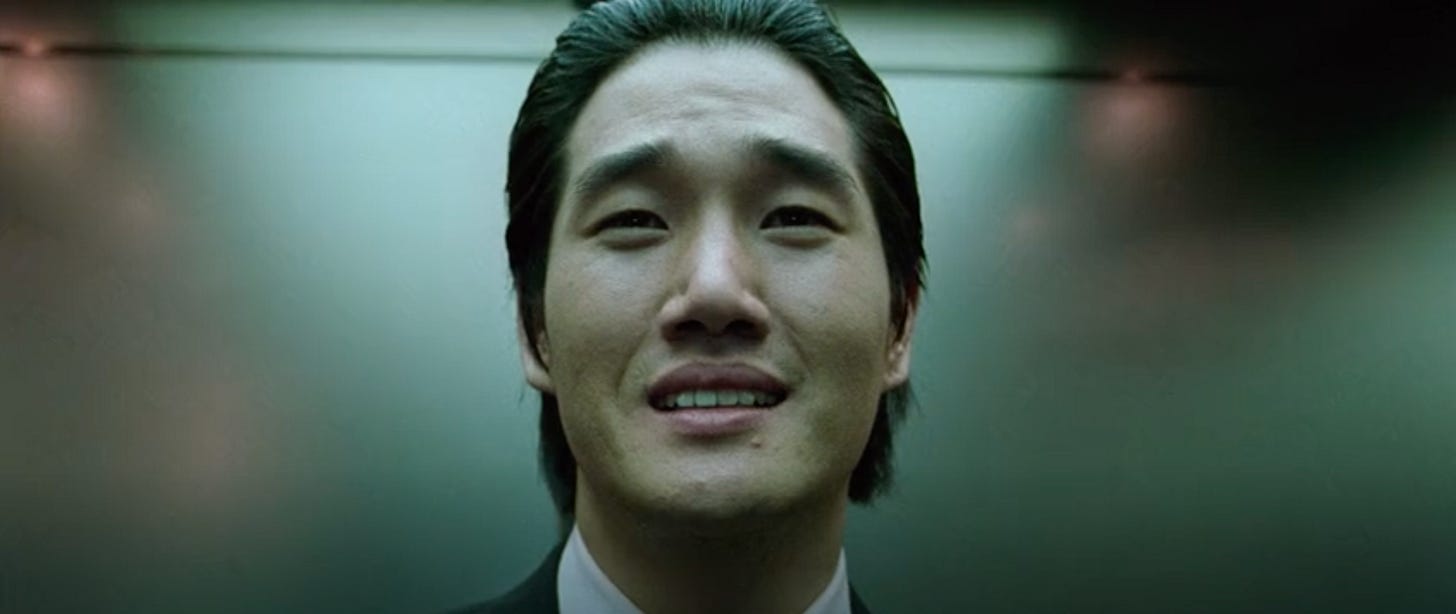

The irony is not subtle, and it’s not meant to be. As the elevator descends, Lee Woo-jin’s composed exterior crumbles. In a symbolic recreation of the memory that has haunted him, he reaches out his hands as if trying to grasp something lost. And then, for the final time—he lets go.

What makes this moment even more haunting is how much it mirrors the film’s opening scene where Oh Dae-su holds another man’s life in his hands. Both characters were given the agency to choose, and both made decisions that led to a lifetime of regret. What if Lee Woo-jin had chosen an alternate path? And what if Oh Dae-su had been a more responsible father? We’ll never know. But Director Park’s message is clear: revenge is a hollow, meaningless pursuit that leaves everyone worse off.

As the credits roll, I can’t help but think back to Lee Woo-jin’s taunting words to Oh Dae-su when they first met: “Revenge is good for your health. But what happens after you’ve had your revenge? That hidden pain probably emerges again.” It’s a brilliant piece of foreshadowing and the perfect summation of this paradoxical, anti-revenge revenge story. There are no winners.

No work of art is without flaws. There’s certainly much to critique about the gratuitous nature of the nudity and how the women in the story serve more as props than fully fleshed-out characters. It could also be argued that introducing the incest trope leans more on shock value than on adding meaningful depth to the story itself. These are all valid criticisms that I would love to explore at a different time. But for now, I’ve written this review to focus on the themes that stood out to me and the lessons we can draw from them.

If you enjoyed Oldboy as well, I hope reading this piece has deepened your appreciation for this work of cinema. See you in the next issue!

Cool stuff to check out 📸

The Bad Kids 隐秘的角落 [TV series]: While playing outside, three children unintentionally capture a murder on film. As they become entangled with the suspect, they uncover a case far more complex than it initially looks.

Why Still Wakes the Deep is an Absurdist Horror Masterpiece [video essay]: A horror game that is so much more than just a game.

Don’t Let People Enjoy Things [essay]: It’s a strange time to be a critic now more than ever.

I Made an Electronic Chessboard Without Turns [video]: You don’t have to be a fan of real-time chess to appreciate this cool piece of engineering.

The Pick Me Paradox: when misogyny comes full circle [video essay]: “Pick-me” if you do, “pick-me” if you don’t. You can’t win.